History of castle Doorwerth

A concise complete history of Kasteel Doorwerth.

Wooden Tower

The castle started out as wooden tower on an island to levy toll, built sometime before 1260, the exact date is not known. This strategic location allows the opportunity to defend the castle. The first known owner is Berend van Dorenweerd.

1260: First Mention and Destruction

The first mention of the Castle is in more unfortunate times when the original wooden structure was besieged and set on fire by the Lord of Vianen in 1260. The Count of Gelre had ordered this to limit the predatory practices of Berend.

Larger and better: Rebuilding of Stone

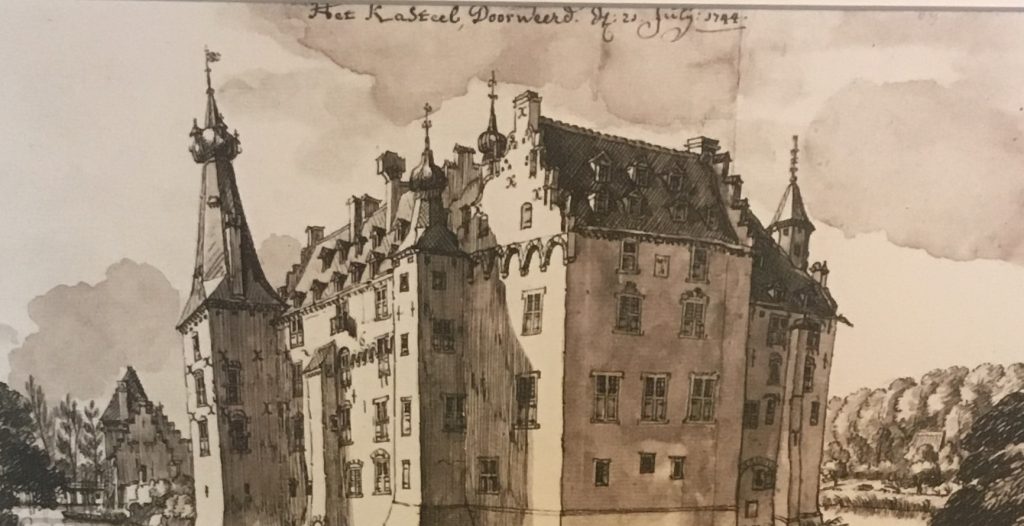

20 years later, in 1280, a rectangular tower with a canal was built by Berend or his son Hendric. It was a water castle or residential tower, made of stone with a size of 10 by 15 meters. The walls were 1.2 meters thick, and the canal that ran around the tower was fed by the Lower Rhine.

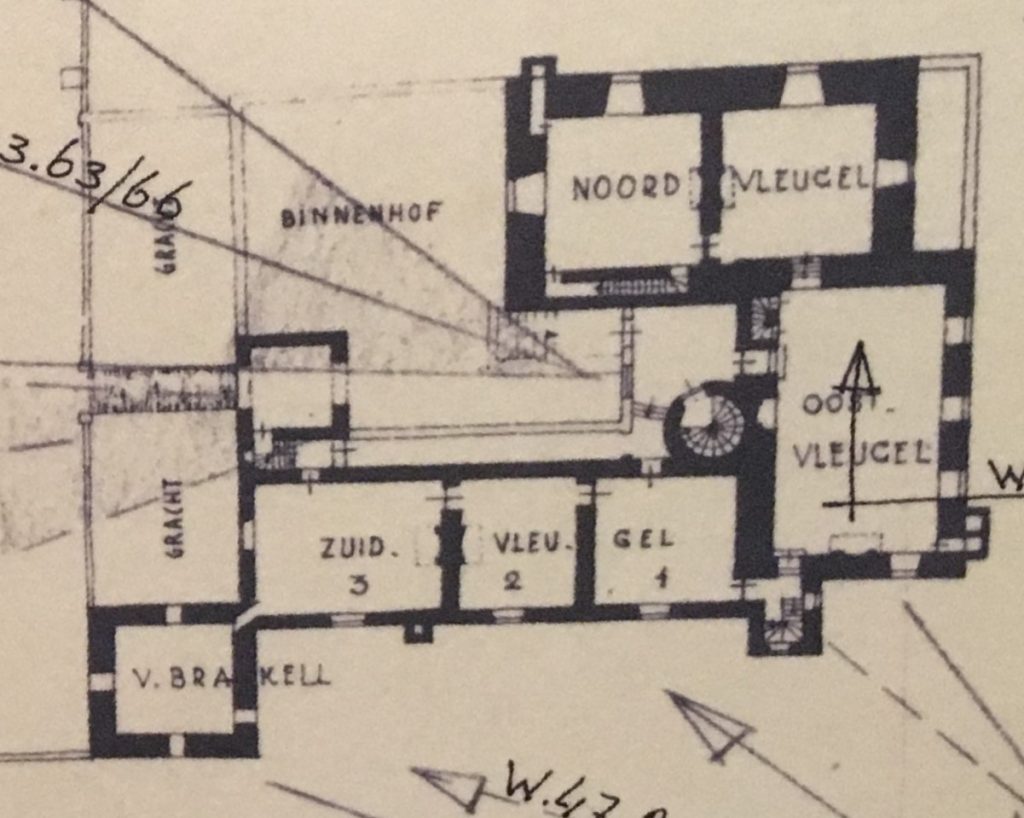

This tower is what we now know as the current East Wing.

1436: Expansions by Reinald van Homoet

Reinald van Homoet enlarges the south wing and moves the main entrance.

There are suspicions that he has also built the massive North Wing. Writings with calculations for a major renovation date from 1435-1436, but it does not mention that this is part of the castle.

1560: Adam Schelleart

In 1560, Adam Schelleart from Obbendorf, lord of Gurzenich, together with his fellow residents, makes the latest changes. Living comfortably became more important after the 16th century.

The south wing was being expanded again and a south-west tower being built. With those changes, the largest size of the main castle was reached.

The last mentioned tower was demolished in the 18th century and rebuilt in the 19th century.

1579: Planting of the Acacia

1579 is the latest year possible the acacia was planted in the courtyard in honor of the Union of Utrecht.

Dikes

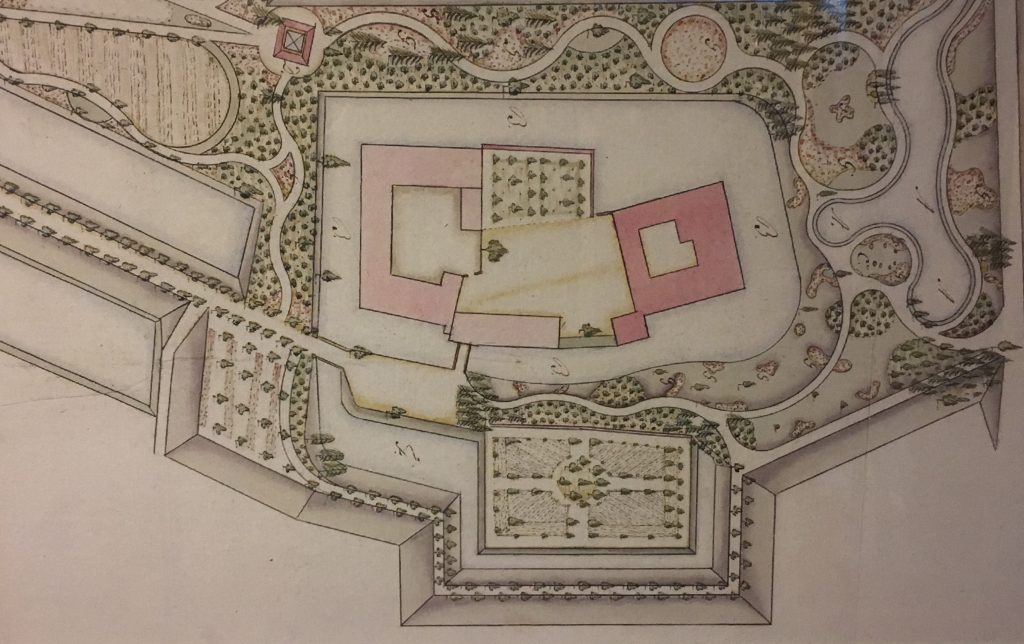

When the Rhine would reach its high point, the land and parts of the lowest floor would flood. To prevent this, a dike was constructed around the castle grounds in 1643, commissioned by Johan Albrecht Schellart of Obbendorf. Dikes gave the lord the opportunity to own more agricultural land, and at the same time it ensured that rivers had less room to execute in the winter. From there on, the lower floors of the castle were dry in winter too.

Not only did he link the castle to the dam with these dikes, there was also a polder and space for a large square garden. So the castle offered what the owners needed at that time; not a well-defensible castle but a castle where one could entertain themself and had the space to receive people.

Gate Building

In the year 1640, the northern corner was renovated and the gatehouse was built by the grandson of Adam, Johan Vincent van Schellaert of Obbendorf.

Anton I, count of Aldenburg

Anton I acquired the castle as Johan’s greatest creditor, though it would never become his main residence. He lived at his castles in Varel and Kniphausen. However, his widow Charlotte Amelie duchess de la Tremoille stayed there after she fleed in 1684.

Disaster year

In the disaster year, 1672, for the Netherlands, Anton van Aldenburg kept the castle intact.

The disaster year was the year that the Dutch War began and the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands was attacked by England, France and the dioceses of Munster and Cologne.

These were also nerve-racking times for castle because the French and the Dutch armies were stationed in the vicinity of Doorwerth.

Case observers

The Aldenburg’s rarely stayed in the castle. At the time, the management of the castle was outsourced to observers, who negotiated the seizure of French troops.

Charlotte Sophie

Charlotte Sophie was born in 1715 in Doorwerth, and was determined to be very gifted in her early teens, writing an essay at the age of 15. She wrote such a large amount of letters throughout her life that she was speculated to have been able to keep a private paper mill busy single-handedly. She was forced to marry by her father when she turned 18, as was customary at the time in order to gain or improve political relationships. She eventually married Willem Bentinck, the son of a good friend of Prince Willem III. Charlotte however, is all but happy; she feels nothing for this man and they end up separating from bed and board, meaning they are still officially married but not bound to each other physically. Their two sons both end up in Bentinck’s custody but end up dying at a young age. Bentinck blames Charlotte, wants revenge and proceeds to reap the finances of the Heerlickheijd Doorwerth. This forced the region into a state of decline, leading Charlotte Sophie to travel Europe in search of aid. In her travels she settles in Germany, in which she becomes a close and long-time friend of the Enlightenment writer Voltaire for 40 years. After this she returns to the run-down Doorwerth, which she attempts to return to its former glory until her death.

Debts

Debt was regularly repaid with the sale of trees and / or pieces of wood land. Both Willem Bentinck and Charlotte Sophie did this. Willem sold a piece of forest for 5300 guilders, and Sophie did this in 1779 when she recovered the rights to Doorwerth after a lawsuit.

The Gardens

Charlotte Sophie hires J.G. Michael to set up the gardens in 1784. Michael probably took 4 years to complete this job, proof of this are several bills paid over those years.

Neglect

After the death of Sophie in 1800, the castle fell into the hands of heirs in England, a grandson and great-grandsons. Because they did not live in it, the castle fell into disuse.

Despite the distance and costs that the castle brought with it, the owners tried to keep it in their possession. Sales of wood and rental had to make this happen.

Definitive name: Doorwerth

During this time, the French held power in these regions. With the registrations that the French performed the name had to be written down into records. Since the owners were English, an English version of the name became permanent.

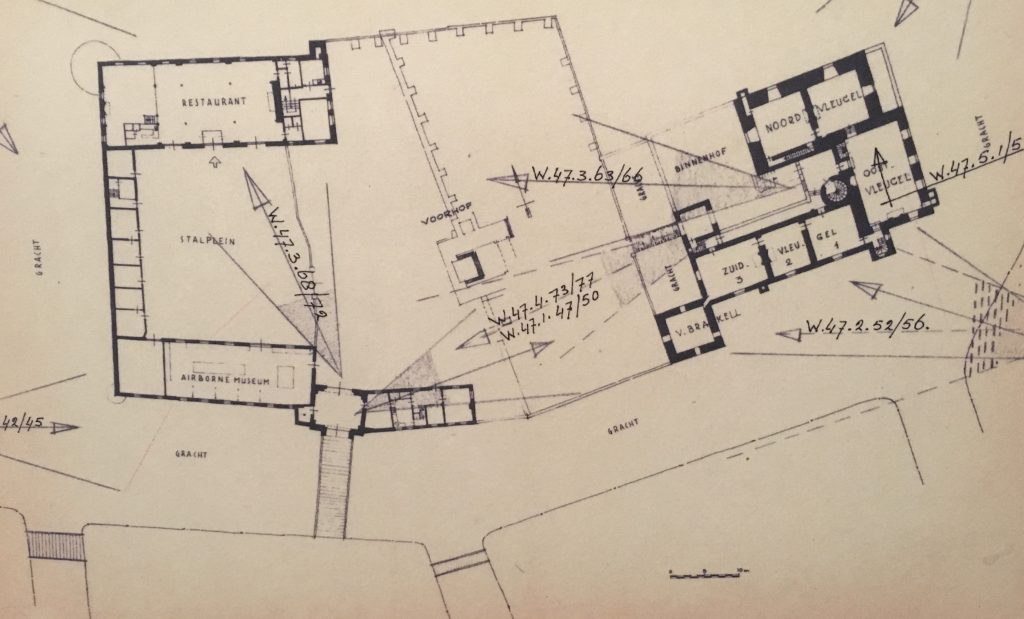

Baron van Brakell

Because the Aldenburg family only rarely lived in the castle, it had slowly fallen into disrepair. In 1837 it was sold to Jacob Adriaan Prosper, Baron van Brakell, who restored the castle with a lot of money and modernized it to the taste of the time. Together with his wife and nine children he brought new life to Doorwerth. On top of investing money, he regularly organized hunting parties and receptions.

Van Brakell was looking for new income with rights that the lord of Doorwerth possessed earlier in time had lapsed.

He had 200 hectares of moorland planted full of pines, what had previously been cut down by the Bentincks.

With the construction of the railway line between Arnhem and Amsterdam, he insisted that a trainstation in Wolfheze was built. To make the trip to and from the station easier, he had the Italian road paved.

He also made it possible to use land for new farmland and factories.

After the death of the widow of the Baron in 1909, the castle once again fell in disuse. The oldest son of the Baron sold the castle in 1910 to association ‘de Doorwerth’.

Adolph Hoefner

Frederic Adolph Hoefer, an old soldier, was the initiator of association ‘de Doorwerth’, an association that buys the castle and restores it. Once restored, the artillery museum of the initiator was installed there in 1913, which later became the Army Museum, one of the first museum in a castle in the Netherlands. The Commandery Netherlands, of the Johanniter Order, also get a place.

Disagreement

The disagreement about the restoration of Kasteel Doorwerth prompted the Dutch Archaeological Association to formulate general restoration principles.

In the Doorwerth castle it was all about disagreement between P.J.H. Cuypers and Victor de Stuers, architecural advisers from the government and Vereniging de Doorwerth. The advisors wanted the entrance gate and hallway to be removed along the south wing. Something that was eventually implemented.

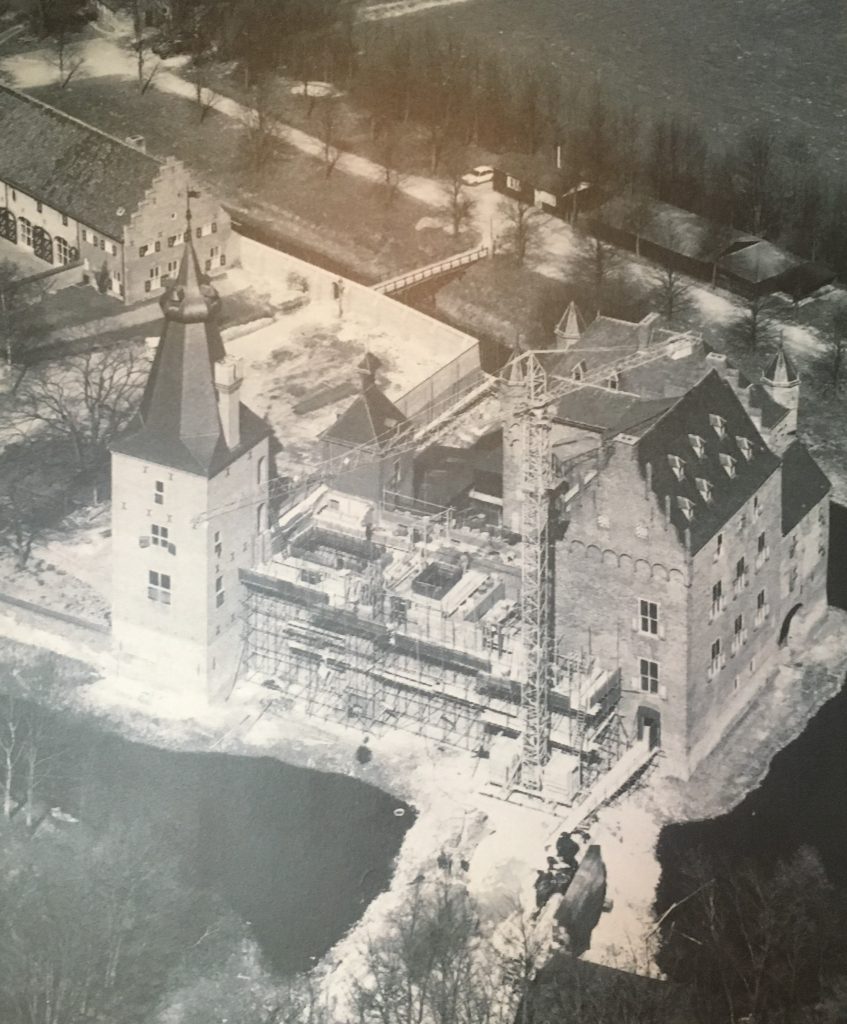

After the war

In 1944 the castle was destroyed by garnet fire. This happened in the aftermath of the battle of Arnhem at the end of September 1944. The ammunition stocks of the German were set on fire and fired on by the Allies.

After the war, the Verenging de Doorwerth took the initiative for restoration. In 1956 the Geldersche Kasteelen took over the management. In 1969 she also got the ownership of castle Doorwerth. For this restoration the situation of the castle of 17th century situation was chosen.

From 1974 the Dutch Hunting Museum took place in the southern wing.

In 1983, a restoration of 37 years is completed, and from that point on the castle could be visited by the public.

Three years later, the castle was opened to the public with Museum Veluwezoom in the east wing.